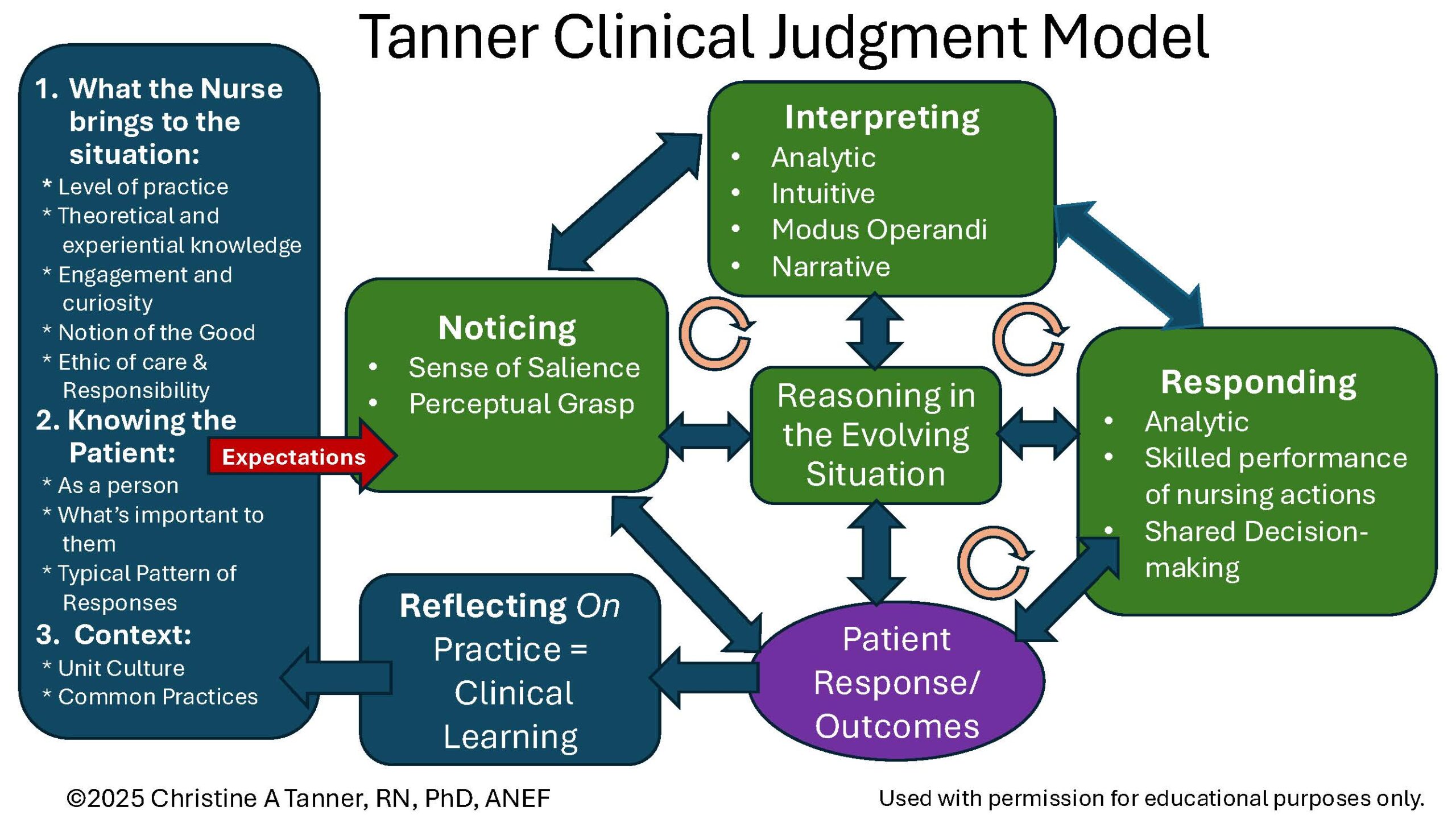

I recently returned from the Educating Nurses: A Radical Transformation 2026 Conference in Las Vegas, where Dr. Christine Tanner delivered a powerful keynote on the updated version of her Clinical Judgment Model (CJM)—first published in 2006 and foundational to contemporary practice.

While the model itself has not changed, Dr. Tanner emphasized something nursing education too often misses: clinical judgment begins with knowing the patient. Caring, compassion, and curiosity are what allow nurses to truly know and understand their patients so that what they notice is shaped by context, relationships, and meaning, not just data.

In a time when first-time NCLEX pass rates are prioritized over developing clinical judgment, her message was a clear reminder that preparing nurses for practice requires more than teaching to a test. It requires forming nurses who engage and know their patients as people, because without that human connection, noticing becomes superficial, and subtle cues will go unrecognized.

Her work challenges us to ask an essential question:

Are we teaching clinical judgment by emphasizing the importance of knowing the patient BEFORE nurses start noticing cues relevant to a patient’s condition?

Tanner’s Clinical Judgment Model is a practice-grounded framework that speaks the language of practice to teach clinical judgment. While many educators are familiar with the four core clinical reasoning steps—noticing, interpreting, responding, and reflecting—recent emphasis from Dr. Christine Tanner reminds us that clinical judgment does not begin with noticing. It begins before the nurse ever enters the room.

Three foundational elements shape everything that follows. Refer to the blue box on the left side of her model.

What the Nurse Brings

First is what the nurse brings to the situation. Clinical judgment is inseparable from professional identity. A nurse’s prior experiences, developing knowledge base, ethical grounding, and commitment to learning from practice all shape how they perceive patient situations. Caring, compassion, empathy, and engagement are not optional traits; they are prerequisites for meaningful noticing. Nurses cannot recognize what matters most if they are disconnected, overwhelmed, or see nursing practice as task completion.

Dr. Tanner reminds us that nurses must first care like a nurse before they can think like one. This ethic of care is rooted in the inherent value of human life and the responsibility nurses accept when they enter the profession. When students are stressed and operating in survival mode, this dimension is often underdeveloped, directly limiting clinical judgment.

Knowing the Patient

Second is knowing the patient. True noticing requires forming a relationship. Nurses must see patients as whole individuals, understand what matters to them, and recognize patterns over time. Subtle cues—the kinds that often signal early deterioration—are invisible to nurses who lack this deep understanding of their patients. Clinical judgment is inherently relational, not transactional.

Context of Care

Third is the context of care. Unit culture shapes individual nurses’ judgment. Psychological safety, incivility, and interprofessional norms all influence whether nurses feel supported in asking questions, seeking clarification, and advocating for patients. These contextual factors are not background noise; they directly affect how nurses think and act.

Clinical Judgment Can Now Begin

Only after these foundations are in place do we move into Tanner’s four clinical reasoning processes.

Noticing is about salience—recognizing what is most and least important in the moment. It is informed by expectations, prior knowledge, and the nurse’s perceptual grasp or essence of the situation.

Interpreting involves analyzing what those observations mean. Nurses compare current findings with expected patterns, recognize trends, and consider possible explanations.

Responding is action in the moment. In Tanner’s original CJM, Reflecting On Practice was placed fourth among the clinical reasoning processes. Dr. Tanner emphasized that we need to make it clear to our students that reflecting on practice immediately follows responding. After every intervention, reflecting on the effect of the response must be done to determine whether the patient’s response is expected or unexpected.

Responding also includes prioritizing interventions, implementing care, communicating concerns, and adjusting plans as patient responses evolve. Responding requires anticipation—knowing what should happen next and being prepared if it does not.

Reflecting On Practice is the nurse reflecting on judgments made while providing care, which deepens learning, strengthens judgment, and prepares nurses to advance in their expertise.

It must be noted that Tanner’s model is not linear. Nurses often move back and forth between noticing and interpreting, responding and reflecting as new information emerges.

This dynamic, iterative process reflects how nurses actually think in practice. It stands in contrast to linear models such as the nursing process or the NCSBN Clinical Judgment Measurement Model (CJMM), which was never designed to teach students bedside reasoning, but only to evaluate clinical judgment using multiple-choice questions on the NCLEX.

The NCSBN CJMM serves an important purpose—it measures judgment for licensure testing. But it does not speak the language of practice (recognize cues/prioritize hypotheses). When educators use test-based language to teach clinical reasoning, students learn to perform for evaluation rather than reason for patient care.

Tanner’s original model was built from nearly 200 research studies examining how nurses think in real clinical settings. It captures the complexity, uncertainty, and responsiveness required for safe practice. That is why Tanner’s CJM must remain central to how we teach students to develop clinical judgment.

TEACH using Tanner’s, TEST using the NCSBN CJMM.

How to Improve Practice Readiness

If we want to develop practice-ready nurses, situated coaching in real-time during clinical must become a priority teaching intervention.

This does not require lengthy conversations. One- to two-minute check-ins at the bedside; early, mid-shift, and late—can transform learning when guided by the right questions:

- What are you noticing right now?

- What was expected or unexpected?

- What do you need to know next?

- What does this change mean?

- What are your nursing priorities, and why?

Making Caring Visible

Can caring be taught? I believe it can, but first, caring needs to be properly defined. In the book Primacy of Caring, Patricia Benner and Judith Wrubel presented this beautiful definition of caring as a nurse:

“The essence of caring as a nurse is that you recognize the value and worth of those you care for and that the patient and their experience matter to you.”

This definition captures why a nurse must care; every person has eternal value and intrinsic worth. I prioritized sharing this definition with my students and showed them how to apply it in practice.

Two Caring Questions

Using this definition, I developed two questions to apply this definition to practice. Each student was asked these questions consistently each clinical or in post-conference:

- What is your patient likely experiencing/feeling right now in this situation?

- What can you do to engage yourself with this patient’s experience, and show that he/she matters to you as a person?

By asking these two questions, despite being task-oriented, my students had caring on their patient care radar and were prepared to honestly answer this question.

Post-conference should be used to reflect on real clinical experiences, not complete busywork. Case presentations, prioritization exercises, SBAR practice, and guided reflection allow students to learn from practice.

To make what Dr. Tanner shared in her keynote stick, pause and ask yourself:

- How are you teaching the importance of knowing the patient, compassionate care and nurse engagement alongside clinical reasoning?

- How often do your students articulate what they are noticing at the bedside?

- How often do you meet with students to coach at the bedside during clinical?

- Does your clinical paperwork reflect the language of practice or the language of testing?

Closing Thoughts

Nursing has always been a practice-centered profession rooted in service, compassion, and responsibility for human life for over 2000 years. When we teach students to reason like nurses—grounded in care, relationship, and accountability—we honor that legacy.

If we prepare nurses for practice, licensure success will follow. The path forward is not more content or better test strategies. It is a clearer purpose, stronger coaching, and the courage to teach nursing the way it is actually practiced.

Recommended Resources

Can Caring Be Taught? This article by KeithRN provides practical strategies to make teaching caring visible in the clinical setting.

References

Tanner, C. A. (2026, January 16). Coaching toward clinical judgment [Keynote presentation]. Educating Nurses: A Radical Transformation 2026 Conference, Las Vegas, NV.

Tanner, C. A. (2006). Thinking Like a Nurse: A Research-Based Model of Clinical Judgment, Journal of Nursing Education, 45(6), 204–211

Keith Rischer – Ph.D., RN, CCRN, CEN

As a nurse with over 35 years of experience who remained in practice as an educator, I’ve witnessed the gap between how nursing is taught and how it is practiced, and I decided to do something about it! Read more…

The Ultimate Solution to Develop Clinical Judgment Skills

KeithRN’s Think Like a Nurse Membership

Access exclusive active learning resources for faculty and students, including KeithRN Case Studies, making it your go-to resource.